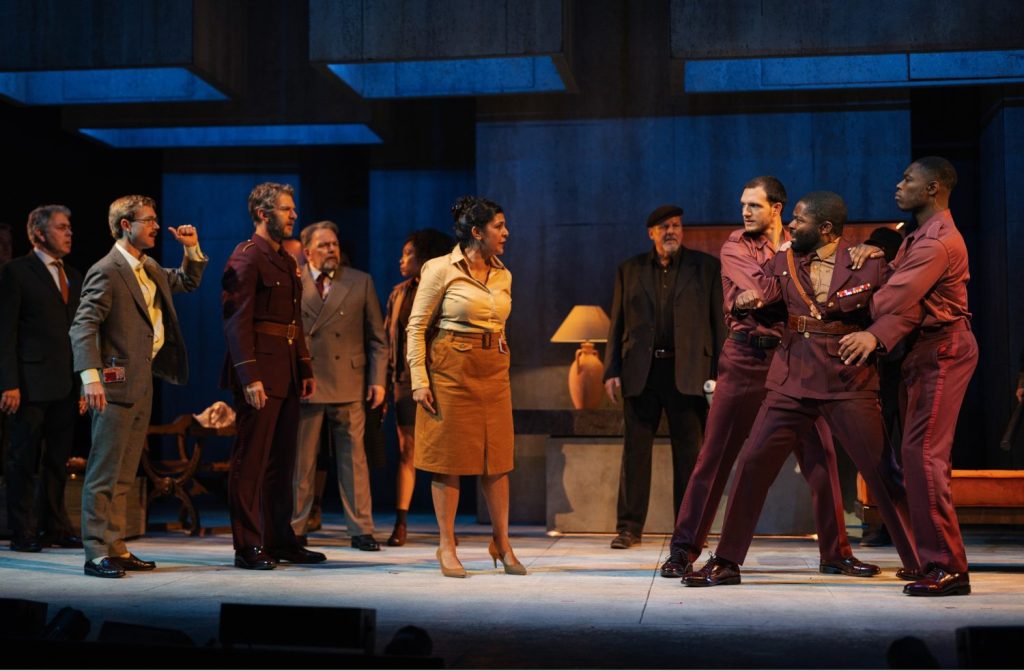

Photo by Misan Harriman.

Coriolanus by William Shakespeare – National Theatre (Olivier), London

Lyndsey Turner’s production of Coriolanus begins not in the street, but in a high-end museum of antiquities where a reception is being held for wealthy dignitaries. The revolting citizens spray graffiti on a Roman wolf statue and confront a suited figure with a glass of champagne: David Oyelowo at Coriolanus. His initial appearance is more mild-mannered than the traditional portrayal, but it is a clever piece of direction. Clearly one of the patricians from the start, Oyelowo is an operator who fits in with the system, but soon begins too lose his cool. His transformation into a demagogue, bringing down everyone with him as he heads towards ultimate disaster, is a brilliant performance.

It is a long-overdue return to the British stage for Oyelowo who, having played Henry VI in the RSC’s early 2000s histories cycle and a breakthrough in Spooks, left for the US where it was much easier for a black actor to find work. The fact he is back is cheering, and Coriolanus shows how much we have missed his skills. He finds ways to make one of Shakespeare’s least likeable characters sympathetic, and also increasingly disturbing. Patricia Nomvete, as his mother Volumnia, is a cold and self-interested character, more interested in the theory of war and heroism than her son, and ultimately motivated to save herself. It seems that Coriolanus is seeking a father, who Shakespeare does not mention. His love/hate relationship with mortal enemy Aufidius – Kobna Holdbrook-Smith, who seems to know Coriolanus will be the death of him – is often played as sexual attraction, but it could be that he is seeking a father figure to validate his reckless behaviour.

There are consistent ensemble performances all round from a play that is always about the reaction of the crowd. Peter Forbes plays a helplessly torn Menenius, who cannot fill the gulf in Coriolanus’ life depsite his best efforts, and Kemi-Bo Jacobs brings cold fury to the rather thankless part of his ignored wife, Virgilia. Es Devlin’s stunning set is also a star. She has created brutalist a concrete frame, mirroring the National Theatre, which hovers above the stage to create a chic, yet looming, gallery, or lowers to the ground to become a hidden labyrinth of claustrophobic chambers. Turner’s staging of the play’s final moments, with a Christ-like image of the dead Coriolanus projected onto the sheer concrete wall of the set, boldly advance the play from its grim final scene. Oyelowo, stabbed to death by a mob second before, is immediately transformed in death into a hero. A statue of him appears in the museum of classical antiquities, and a 21st century child stops to stare. It is not what happened that matters: it is how the story is presented.