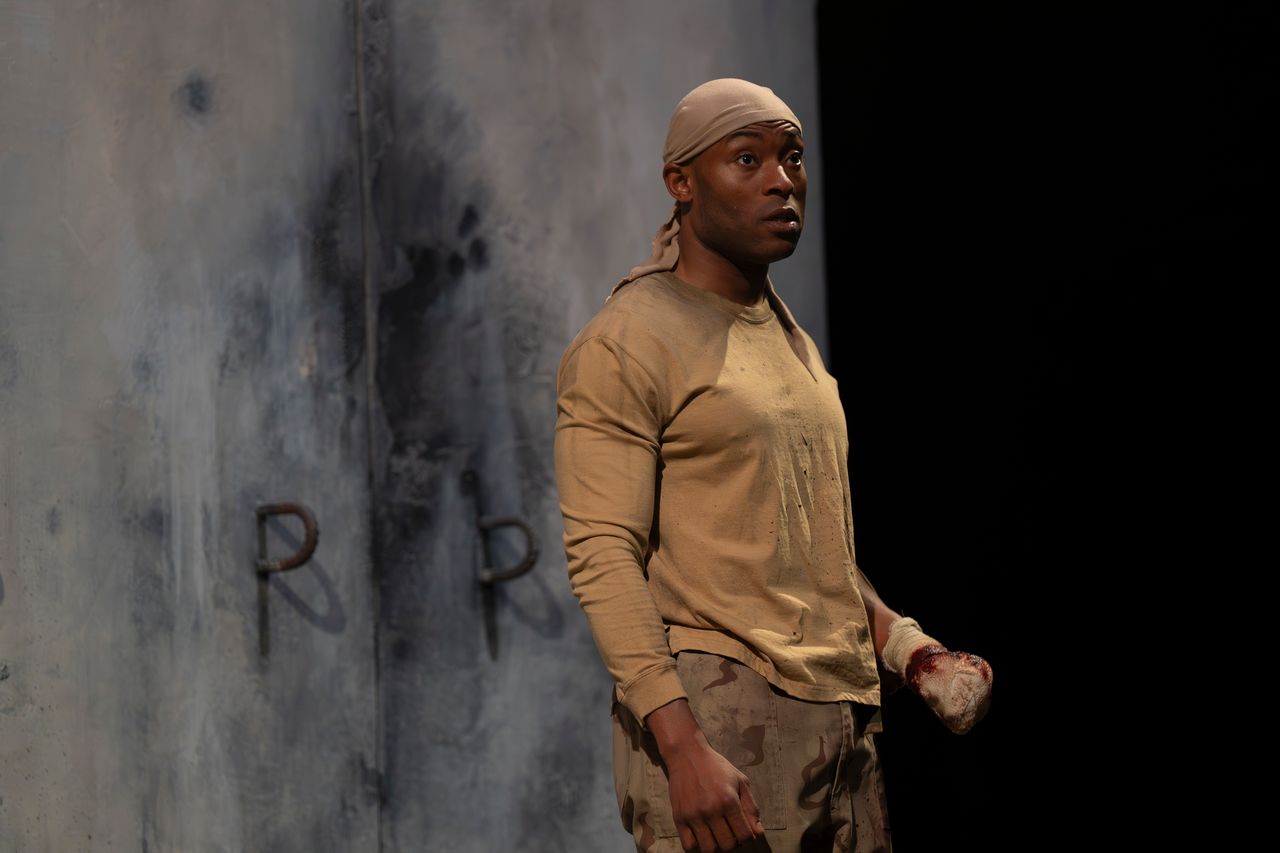

Arinzé Kene and Kathryn Hunter. Photos by Ellie Kurttz .

Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo by Rajiv Joseph – Young Vic, London

Published at Plays International

Rajiv Joseph’s play, which premiered in Los Angeles in 2009, is revived by Young Vic artistic director Nadia Fall as part of her first season. It deals with a world at war, physically and culturally, but the context is the US invasion of Iraq, now more than 20 years ago. It is obvious why Fall, and director Omar Elerian, think ‘A Bengal Tiger at Baghdad Zoo’’ may have something to tell us, nearly a generation on, helping us reflect on how little we seem to have learned from the mistakes of the past.

The show opens in the ruins of Baghdad Zoo, illuminated by the scope torches of two US soldiers, Tom (Patrick Gibson) and Kev (Arinzé Kene), as they discover a tiger still prowling its concrete enclosure. The tiger, played by Kathryn Hunter, has a better perspective on humans and war than any soldier, or indeed the lions of whose intelligence she takes a very dim view. Soon, Kev has shot her dead after she takes off Tom’s hand, and she begins an afterlife, inhabiting the play as a ghost. ‘A Bengal Tiger…’ is a reflection on war and conflict, with hefty doses of both brutality and absurdity. In some ways it is an old-fashioned play, reminiscent of non-naturalistic post-war dramas such as John Arden’s ‘Sergeant Musgrave’s Dance’. Its characters are types, rather than individuals, representing different aspects of a conflict which, deeply controversial at the time, has come to seem less forgivable with each passing year.

The two soldiers are at the heart of the play. Patrick Gibson plays Tom with obnoxious conviction as shallow, aggressive and avaricious, coveting a gold gun and a gold toilet seat looted from the palace of Uday Hussain, Saddam’s son. Arinzé Kene has the better part as Kev, who is staggeringly naïve and child-like, and he inhabits the role in a way that seems almost eerie at times. The play is very episodic, moving between set pieces. Uday himself makes several appearances as a ghost, having been gunned down by US troops, and is played with triumphant glee by Sayid Akki, whose stage presence is remarkable for an actor with only two previous credits in his CV. Ama Haj Ahmad, as Uday’s gardener Moussa, now working as translator for the US military, brings humour and despair to his role in equal measure.

The titular tiger was to have been played by David Threlfall, who had to temporarily withdraw with illness. Kathryn Hunter stepped in at the very last moment, to the extent her lines are provided on monitors in the auditorium, but you would never know it. In a cast that is uniformly excellent, her charisma stands out in a way that captivates the audience. She uses her physicality with apparent ease to embody a tiger, casually twitching her tail, while conducting an annoying existential debate with the audience about moral responsibility. She has real star power.

While the cast give their all, and director Omar Elerian powers the play along, it is nevertheless flawed. Some grim scenes that illustrate the horrifying impact of the conflict, and the brutal Hussain regime, on everyone from teenage girls to soldiers, leave us in no doubt about the war. Joseph is scathing about the arrogance and venality of the US troops, and the sinister love of torture exhibited by Uday. However, the philosophical commentary offered by the tiger, and the metaphysical elements of the play seem overblown and lacking in depth, while the episodic nature of the narrative reduces it to a set of show pieces. Hunter’s late casting is fortunate, because the play would otherwise feature just two women in bit parts, as a sex worker (Sara Masry) and a mysterious leper (Hala Omran). The appearance of the latter, singing an atmospheric but untranslated Arabic lament, seems like superficial cultural exoticism.

Rajha Shakiry’s broken concrete set and Jackie Shemesh’s lighting, with night scopes and ceiling fan shadows, are imaginative and effective. The Young Vic has given ‘A Bengal Tiger…’ an excellent production, but it does not make a convincing case that this is a play that stands up to scrutiny many years on, or tells us anything new about a time we risk forgetting.