How It Is (Part 2) by Samuel Beckett – Coronet Theatre, London

Published in Plays International

Irish company Gare St Lazare were booked to perform at the Coronet Theatre when the pandemic struck in 2020, depriving London audiences of the greatly anticipated second instalment in their stage adaptation of Samuel Beckett’s 1961 prose work, ‘How It Is’. The book is divided into three parts, and the first was seen at the Coronet Theatre in 2018 while Part 2 premiered in Cork in 2019. In a much-delayed transfer, it finally arrives in Notting Hill where it proves well worth the long, long wait.

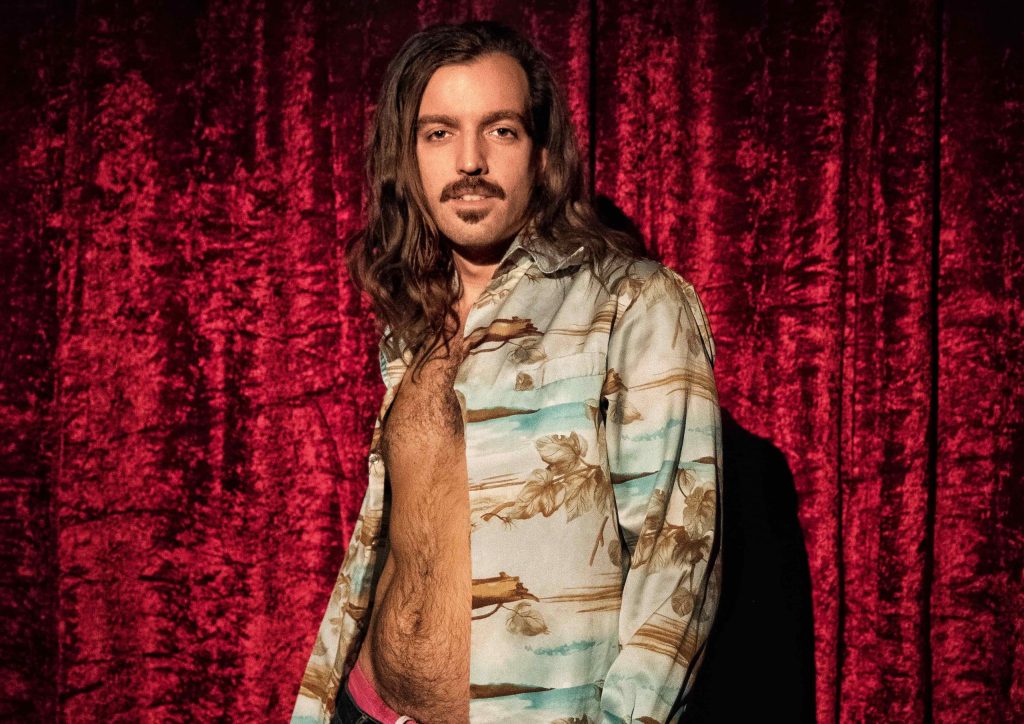

First published as ‘Comment c’est’ in the same year as ‘Happy Days’, Beckett’s final full length prose work was not written for the stage and could easily be viewed as unstageable. Gare St Lazare have no such qualms and tackle its rhythmic, at times almost abstract, monologues with a complete conviction that results in a piece of theatre that is in equal parts entirely absorbing, extraordinarily demanding, and unlike almost anything else seen on a stage. Continuing where the first production left off, two actors – Stephen Dillane and Conor Lovett – describe their experiences lying side-by-side, face down in the mud, unable to speak aloud, hardly able to move, and sustained by sacks of tinned food. Part 2 is introduced by the unnamed narrator (Dillane) who lies beside Pim (Lovett) and tells us what happens: “My time. My life. In the dark. In the mud. With Pim.” Then we hear from Pim, who takes up the narrative from his own perspective. The actors alternate long streams of consciousness, expressing themselves in truncated sentences that Pim describes as “Short blurts. Midget grammar.” Beckett’s highly stylised writing is like a form of verbal minimalism, repeating phrases, circling and returning, the same yet different. It is a mesmerising experience.

The performance also includes a gamelan orchestra – specifically the Irish Gamelan Orchestra. Their instruments completely fill the stage with banks of gongs, bonang drums that look like cooking utensils, and xylophones. There is a singer, woodwind and strings, including an eerie, scraping rebab that sounds as though it is broadcasting from another time. Multiple musicians materialise and vanish, playing pieces of strange, deeply atmospheric music that fills the theatre. The conjunction of gamelan and Beckett is, on the face of it, very odd but in practice seems to make complete sense. The rhythms of text and music respond to one another, mutually reinforcing their power of communication. The orchestra is led by Mel Mercier, a long-term collaborator with Gare St Lazare, who acted in Part 1. He kneels at a drum shouting out mysterious number sequences that somehow control the polyrhythms flying around him. It is like a classical orchestra on acid.

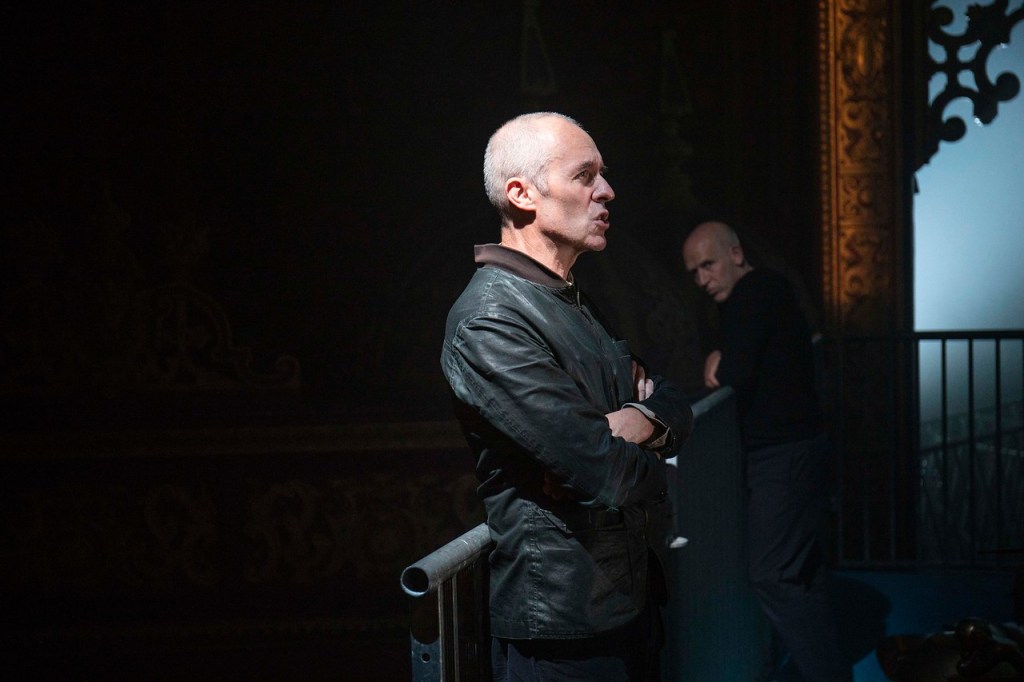

The production is directed and designed by Judith Hegarty Lovett, joint company director with Conor Lovett. Her vision is unmistakable, a staging that locates the two performers around the edges of the Coronet’s magnificently decayed auditorium. Dillane first appears draped at an uncomfortable angle over the aisle handrails, spotlit against flaking paintwork. He and Lovett perch awkwardly behind the orchestra, lie on the floor behind the gong racks, and appear in the audience. They are never centre-stage, as they struggle to communicate their bizarre predicament from the sidelines. Yet they cannot stop talking. The words flow from both without ceasing, beyond their control, and they spend around half the evening attempting to conclude what they have to say.

Both performances are astonishing. The evening runs, remarkably, for more than 150 minutes with an interval and involves feats of memory that put almost any other stage roles in the shade, including Beckett’s own, notorious challenging monologue ‘Not I’. Conor Lovett’s Irish accent is soft, lyrical and in tune with the poetry of Beckett’s phrases. Stephen Dillane, contrasting English in his delivery, attacks the lines, as though speaking despite himself. Lovett at times bounds across the stage with a weird delicacy, while Dillane strikes strange formal poses that appear unrelated to what he has to say. At one point Dillance grabs a lectern and delivers an imaginary commentary on what they are doing, at double speed, written by a “witness” who he then concludes cannot exist. They take a tea break halfway through, in real time, boiling a kettle and making and drinking cups of tea while muttering to one another, as the audience looks on. Both actors are both disconcerting and completely captivating, giving the performances of their lives.

The scenario of ‘How It Is’ is like a more extreme version of Winnie’s predicament in ‘Happy Days’, half buried in a way that is both symbolic but also entirely real. The narrator and Pim describe the contortions involved in reaching objects and each other, in moving and communicating while face down in the mud. Disturbingly, their relations quickly turn to violence. Pim subjugates the nameless narrator, conditioning him to respond to unspoken commands delivered with nails to the armpit, a tin opener to the buttocks, a smack on the skull and finger up the arse. Beckett’s world is figuratively as well as literally dark, a place where only two men are required to ensure inequality, exploitation and oppression. This is what passes for communication, until Pim discovers that he can trace words on his companion’s back which he can eventually decipher. The two characters seem to become one another as they demand narratives of “life above”, which emerge in dark, alarming fragments – a half-remembered life in the building trade, married to a woman who jumped from a window. Beckett’s language is coarse as well as mesmerising, never allowing the audience’s expectations to settle. The question “Do you love me, c***?”, scraped into a bare back, is as close as he comes to anything life affirming. Yet the basic truth is that, despite everything, both characters are still alive, and as long as they are alive they can speak.

At the end of an astonishing evening, time having long since lost its meaning, we emerge wondering what we have seen and what it could signify. Beckett offers no easy answers, and probably no answers at all, but he exposes the nature of being in a way that few other writers have attempted. Fifty years after this work was written, it still provides the most difficult and disconcerting experience theatre has to offer. How It Is (Part 2) is not for the faint hearted. It is, however, made for anyone who wants to see artists who are completely committed to an entirely original vision, a show that demands everything from its audience as well as its performers, a company that is working on the cutting edge of world theatre, and work of the highest quality. Serious credit must also go to the uncompromising Coronet Theatre, and its artistic director Anda Winters, for staging work that few theatres would contemplate. Gare St Lazare deliver an experience few will be able to forget.