The Comedy of Errors by William Shakespeare – Barbican Theatre, London

Like all theatre companies, the Royal Shakespeare Company has experienced a tough 18 months, so it is fortunate that artistic director Gregory Doran’s complete cycle of Shakespeare’s plays, derailed by the pandemic, had reached The Comedy of Errors when the curtains went down in 2020. No Shakespeare play is better placed to provide the pure entertainment that has proved a hit with returning audiences. Directed by Philip Breen, now established as the RSC’s comedy specialist, the production transfers from Stratford-upon-Avon, where it played in the temporary Garden Theatre. Honed in the open air with nowhere for the actors to hide, it is a riot.

Breen and designer Max Jones have conjured a 1980s Ephesus, overrun with gleefully realized costumes. Dresses are teal, tights are cerise, shirts are splashed with geometric pastels, and braces are in evidence. Military uniforms are in fetching pale blue or green from a Tintin fantasy South American republic. Pale stone walls and a chequered marble floor suggest a Mediterranean setting, but the ambience is that of a parallel, heightened, frantic version of reality.

The mood is carefully balanced between oppression and anarchy. The chill of the first scene, as Antony Bunsee’s gaunt, abject Egeon is sentenced to death for passport offences, dissolves as the dignity of the Duke of Ephesus and his courtiers is dismantled in the escalating chaos. A few scenes are needed to wind up the tension caused by the confusion between two sets of identical twins – the Antipholus brothers and their servants, the Dromios. Hedydd Dylan’s excellent Adriana, pregnant and furious, marches on her supposed husband and, haloed in hairspray, delivers an inspired rant about fidelity. From then on, the production cannot be stopped.

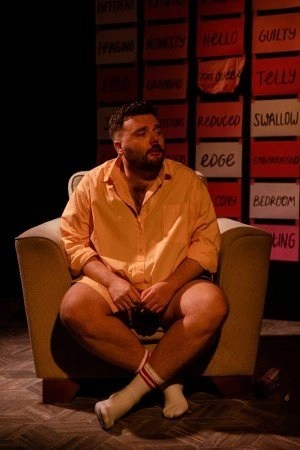

The pairs of twins are passably similar in appearance but are distinct characters. Guy Lewis plays Antipholus of Syracuse, newly arrived in town, as the naive victim of events beyond his control. Rowan Polonski’s Antipholus of Ephesus is all sharp suits and moneyed front. This makes it all the funnier when the provocations finally become too much and he loses it completely, leaping about in a manic fury that terrifies the entire theatre. Breen carefully builds the farce to a sustained peak, releasing the tension in a series of sustained physical comedy masterclasses. Lewis spends an entire scene wrestling an officer into increasingly unlikely positions, while trying to explain himself to Dromio. Polonski’s star appearance at a ribbon-cutting ceremony is derailed with inventive use of the scenery. Lewis and Broadbent turn hoary jokes about an amply proportioned kitchen maid into a strange stand-up routine. A live barbershop quartet soundtracks the entire performance, as much part of the action as the rest of the cast.

Jonathan Broadbent, as Dromio of Syracuse, is initially more suave than his twin (played by Greg Haiste), who is always heading for a pratfall. His disintegration in the face of provocation is a delight, but the two also share a surprisingly moving final reunion scene. The darker aspects of the play are also highlighted, masters and mistresses showing a disturbing tendency to beat them both at every opportunity.

The production features many other enjoyable performances. Avita Jay’s Luciana is the beleaguered, outraged voice of normality. Baker Musaka has a lot of fun as Angelo, the goldsmith, first saucy then outraged then fearful, as he is menaced by “merchants” to whom he owes money. These come in the inspired form of criminal boss William Grint, a deaf actor who signs his lines, and his Russian bodyguard (Dyfrig Morris) who interprets his threats, which are made in gory dumb show. Riad Richie makes the most of his background role as a guard with scene-stealing antics that turn him into an audience favourite. Toyin Ayedun-Alase’s Courtesan wears a full Grace Jones catsuit and hair, and has the presence to match.

Farce is a difficult genre to get exactly right, but Breen does the play and the company proud. His awareness of RSC history, handled lightly, brings an extra layer of pleasure: a black and white chequered shopping bag, a tribute to Ian Judge’s wild 1990 production, or the ginger Dromios, reminiscent of Jonathan Slinger and Forbes Masson in Nancy Meckler’s 2005 version. His production brings people together in the shared enjoyment denied for so long, but also succeeds in drawing out impressive nuance from a play that can seem shallow in the wrong hands. The final scenes bring the mood down from high farce to an almost Winter’s Tale-like redemption, as the reunited twins circle each other in wonder and their family reappears all around them. It is the culmination of a triumphant evening, and a production that has the quality to fill the Barbican up again.