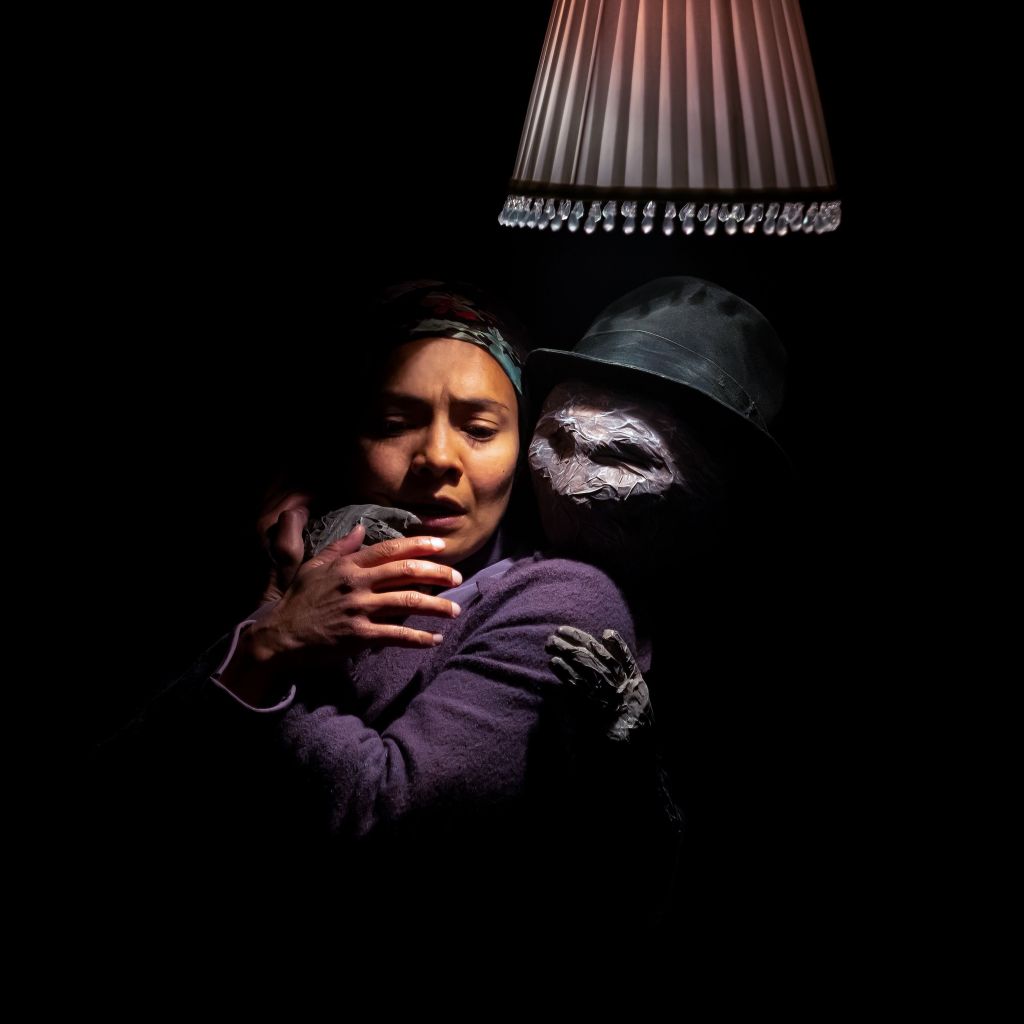

Vanessa Guevara-Flores. Photo by Mark Sepple.

Kin by Amit Lahav – National Theatre: Lyttleton, London

Published by Plays International

Founded in 2001, Gecko Theatre are a collective with an unmistakable style born, literally, from years of preparation. Remarkably Amit Lahav, founding artistic director and performer, spends at least three years with his performers researching, exploring ideas, and storyboarding to develop a show. The latest, Kin, was commissioned by the National Theatre and explores migration and ideas of home.

The cast of nine transform from a cohort of drunken border guards into groups seeking refuge and experiencing the fear and humiliation of rejection. Gecko perform in a style that fills a gap you never knew existed between contemporary dance and theatre. They move in highly stylized ways that are dance-based but illustrative, and always strangely compelling. The cast advance like fencers, stride in low lunges, sway together like a field of wheat in the wind, and pile themselves into a celebratory tower. They dance constantly.

Movement is at the heart of Kin, but there is language too: just not in the way we have learned to expect on stage. Characters talk constantly, but in multiple different languages from around the world. These are the mother tongues of the cast members, whose stories of immigration the show tells. They range from an escape from Yemen to Palestine in the 1930s to scenes escaping conflict and taking small boats that relate to what is going on right now around Europe. We may not speak the language, but the audience has little doubt what is happening. When a single segment of English breaks into the verbatim accounts of being a refugee, it hits hard.

Kin also has an impressive visual impact which ties its themes together. The stories spread across nearly a century, but the overall look is very Gecko, with mid-20th-century costumes (by designer Rhys Jarman) and middle European music (composed by Dave Price) – Kafka and klezmer. It translates cleverly to the large Lyttelton stage which is a dark space illuminated by pools of light, often provided in unconventional ways by lighting designer Chris Swain. At one point a family scene is entirely lit by a small television set, an electric fire, and a standard lamp, carried by characters dancing in a circle. The stage is shaped like an island, white cliffs gleaming around the edges. There are some stunning moments, including a family from India wiping their faces with clothes that turn their skin white.

While repetition is part of the point of Kin, with different generations experiencing the same discrimination, it causes some drift during the middle of the show as narrative threads become harder to distinguish. However, its emotional and political heft cannot be questioned. The final scene, in which the cast tells us who they really are, where they come from, and where they live, is a moving moment.

The issues this show examines – what happens to people caught up in circumstances outside their control who want to find a home – could not be more relevant. With political discourse on immigration in the UK more extreme than at any point in recent memory, the timing is perfect for a play about humanity and the value of human life. Both Gecko and National Theatre director Rufus Norris should be congratulated on bringing this urgent, beautiful, and devastating show to a big stage.