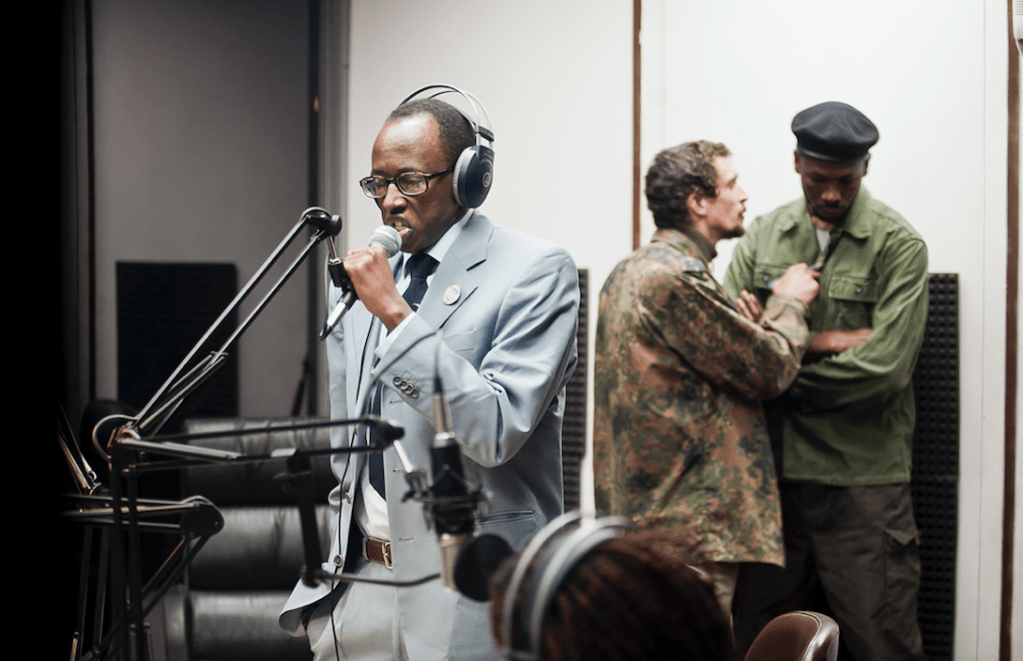

Dickie Beau © Robin Fisher

Re-Member Me by Dickie Beau – Hampstead Theatre, London

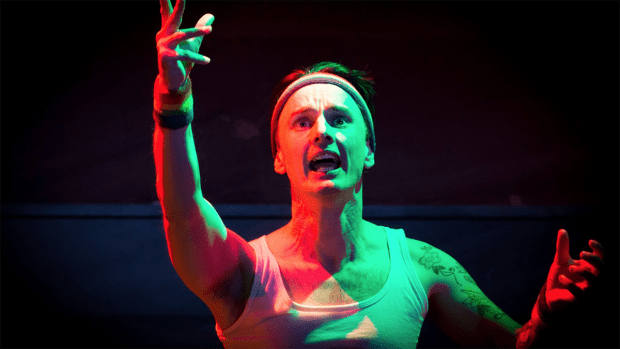

Dickie Beau’s one-man show is an original, charming and clever project. The evening is presented as a theatrical history of, or meditation on, Hamlet and those who have played him. In fact, it is a more a queer history told through the medium of Hamlet. Beau, in full Chariots of Fire running gear plus rainbow headband, is a very appealing stage presence, drawing us into his research – a series of interviews with some of those who worked front and backstage at the National Theatre in 1989. The date is significant because it is when Daniel Day-Lewis dropped out of the lead role in Richard Eyre’s production of Hamlet, still a somewhat notorious theatrical event. But, while this remains well remembered, his replacement by Ian Charleson, of Chariots of Fire fame, who went on to give the performance of his life – perhaps the best Hamlet of them all – while suffering with AIDS and only months from death, seems to have faded from memory, Charleson was the first celebrity whose death was publicly acknowledged to have been caused by AIDS, and his Hamlet an unforgettable experience for those lucky enough to see him, and a social milestone.

Beau’s role in bringing this ignored history to the stage is as an interpreter, not least because he is a lip-sync artist. He takes this obscure stage technique and makes it sing, sliding effortlessly into the words and personalities of interviewees including a hilarious John Gielgud, and Day Lewis’s dresser. The way he channels long-departed characters is almost spooky, and deeply impressive. His interview material is full of insights, including the dresser slipping the cloak from Day Lewis’s shoulders as he weeps in his dressing room to give to a white-faced Jeremy Northam, going on halfway through the show. The one-night only production of ‘Bent’ staged to launch Stonewall, with a heroic performance from an ailing Charleson, is recreated from the memories of those who were present.

The structure of the show lacks a little clarity. A significant amount is pre-recorded and shown on screens, where four Beaus voice conversations about Charleson’s Hamlet between characters including Richard Eyre, Ian McKellen and Sean Matthias. While these play, Beau himself seems wasted as he rearranges the stage, while the screen has similarly to be kept occupied when he is performing live. The Hampstead Theatre’s broad stage is not the ideal setting for a show that would set a smaller venue alight. But it is hard to hold this against a show that manages to be so likeable and funny while performing an important service in educating a new generation about recent history, so quickly forgotten. But Beau, who voices ‘Withnail and I’s Uncle Monty to acknowledge that he “will never play the Dane” should put himself front and centre even more, performing live. He may not be Hamlet, but the audience loves him.