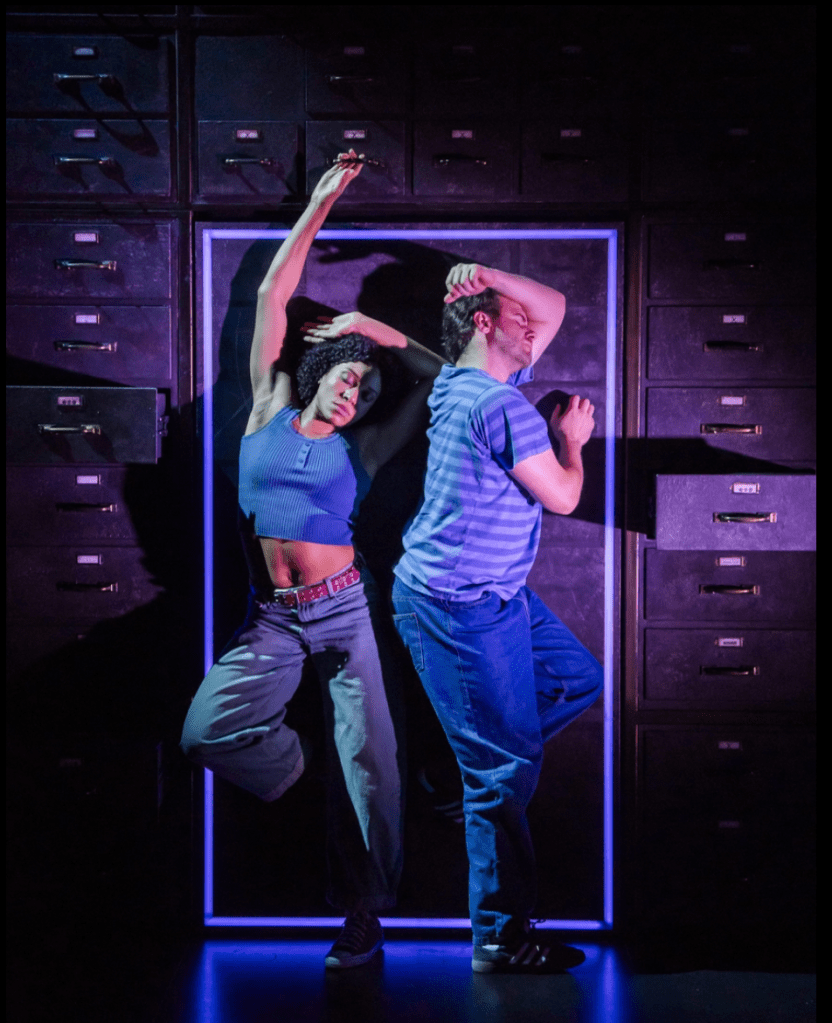

Anna Sinclair Robinson and Joe Layton. Photo by Tristram Kenton

Lost Atoms by Anna Jordan – Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith

Published at Plays International

Lost Atoms, written by Anna Jordan, is the 30th anniversary production for Frantic Assembly, who are a staple of the UK’s 21st century touring scene. Led throughout by Scott Graham, the company is known for making movement the core of their expression, and devising their own method entwining the text and the physical. The Frantic Method has been very influential, shaping a performance style that is very distinctively of our time. Frantic have achieved a great deal, applying their approach to classic text and new writing with equal success. It is all the more impressive that their world is smaller touring venues rather than the big commercial or subsidised theatres, where experimental work that challenges audiences is needed most. It is entirely appropriate that Lost Atoms is a co-production between the Lyric Hammersmith, the Curve in Leicester and the Mayflower, Southampton.

For their anniversary tour they have chosen a new play by Jordan who, since her last play in 2018, has been working on television series such as One Day for Netflix. Lost Atoms is about ordinary living, and what that really entails. A couple meet, get together and go through experiences related to pregnancy which are both common, and unforgettably traumatic. There is a cast of just two: Joe Layton plays Robbie, and Anna Sinclair Robinson plays Jess. Their meeting involves coffee shop wifi, and they get together through a series of chances, gradually working out how much they like each other. They encounter each other’s families, and all they bring – cleverly staged through one-sided conversations. Then Jess gets pregnant. It is impossible to discuss the plot without giving too much away, but what follows tests their relationship to the limits.

There are remarkable similarities with Luke Norris’ play Guess How Much I Love You?, currently playing at the Royal Court, which also has a cast of two, and concerns a relationship beset by pregnancy trauma. However, under Scott Graham’s direction the style of Lost Atoms is very different. Layton and Sinclair Robinson use Andrezj Goulding’s set – a bank of filing cabinets – like a climbing wall. Drawers pull out to become seats, steps, even a toilet, but they also act as drawers, containing props but also memories. A massive slab, looking disturbingly like the door to an ancient tomb, flips up to form a bed, angling the couple towards the audience in mid-air. The physicality of the performers is, at times, mesmerising. They are frequently performing while horizontal, or suspended at gravity-defying angles. They move in relation to one another throughout, expressing the closeness and distance of an intimate relationship through their bodies as much as their words.

The story is told in flashback, as Jess and Robbie explain what happened to them for the benefit, it seems, of the audience. It takes time to get going and the first half, which shows us their developing relationship, tells us less than the second. The performers become more convincing as the stress mounts, and they move away from the sometimes exaggerated naivety of their initial personas. Lost Atoms truly draws the audience in when it starts to explore what happens to people behind closed doors, in cold NHS consulting rooms and tiny flats. We think we know what life is about, but human drama is at its most extreme in everyday settings, just out of sight. Frantic Assembly’s production showcases the strengths of their work, with complete physical commitment to storytelling. Actors do things you may never have seen on a stage before, but which seem strangely natural. Conventional theatre can seem static in comparison.