Krapp’s Last Tape by Samuel Beckett – Barbican Theatre, London

With the pre-announcement of not one, but two future productions of Krapp’s Last Tape scheduled for the mid-2030s (when Sam West and Richard Dormer reach 69, the age of Beckett’s main character), it’s reasonable to ask what makes actors want to play this role so much. To some extent, it could be that recording the lines for younger Krapp at 39 represents a solid investment in future work. But there is also a clear sense that this is one of the big roles, a defining part, and one that suits unconventional actors better than classic leads. Stephen Rea is very much the kind of performer suited to Krapp. Actually 78, although he very much does not look it, Rea bring a hangdog comedy and a deep sadness to a role others have approached with more rage and less stillness. He also met Beckett himself, who attended rehearsals for the Royal Court’s 1976 production of ‘Endgame’ with Rea in the cast.

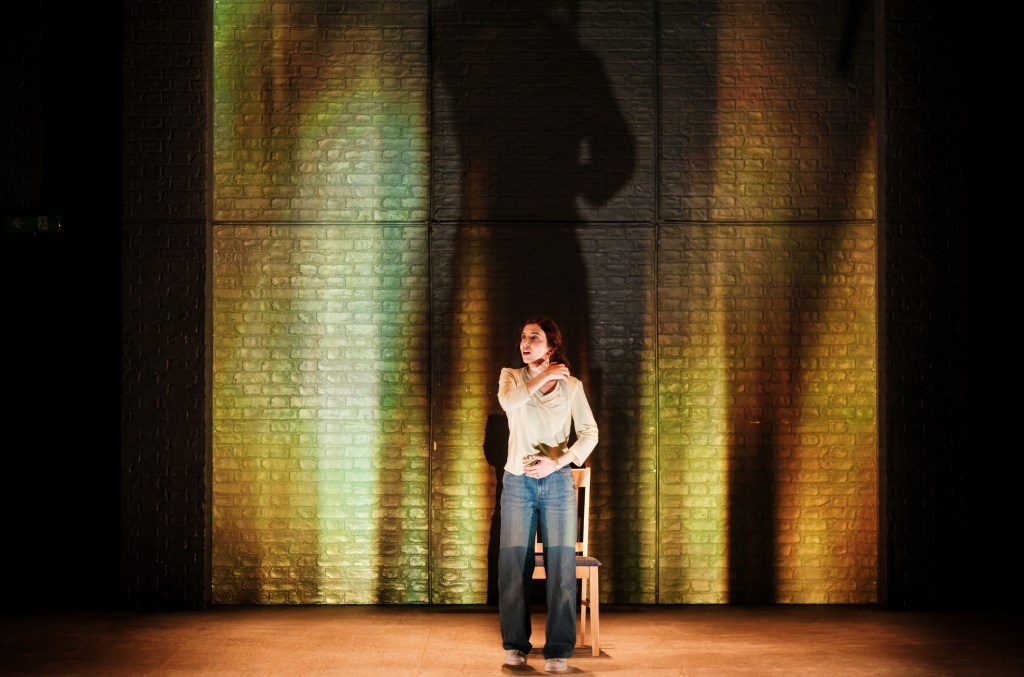

Vicky Featherstone’s production is designed by Jamie Vartan, who places Krapp’s desk in a square of light beyond which lies only darkness. A path of light leads from the desk to a door, beyond which lies smoke, the drink which Krapp retires periodically to consume, with a comic sloshing sound, and who knows what else. The set also aids the silent comedy at the heart of Beckett’s play, in the form of a ludicrously long desk drawer which Krapp pulls out further and further to reach his hidden bananas. Rea plays the sad clown very well, dialling down the slipping on banana skins but emphasising the shambling walk, which looks both exaggerated and weirdly familiar. The inevitable comedy of decay is inseparable from the sadness, loneliness and failure that haunts Krapp, in the form of his naive 39-year old self, still seeking and possibly expecting happiness. His writing, unlike that of Beckett, faded away despite his epiphany in a storm, which he can not longer bear to hear about.

Stephen Rea recorded the Krapp tapes in his 60s, but they sound like the work of a younger man. The weighted precision of his delivery makes very word matter a great deal, to Krapp and to Beckett as writers and to us as an audience. His performance is heartbreaking without ever needing to fully express the emotions we know he is feeling. This play, so slight, remains a work of remarkable power that can bind the entire audience of a large theatre into the unravelling existence of one man.