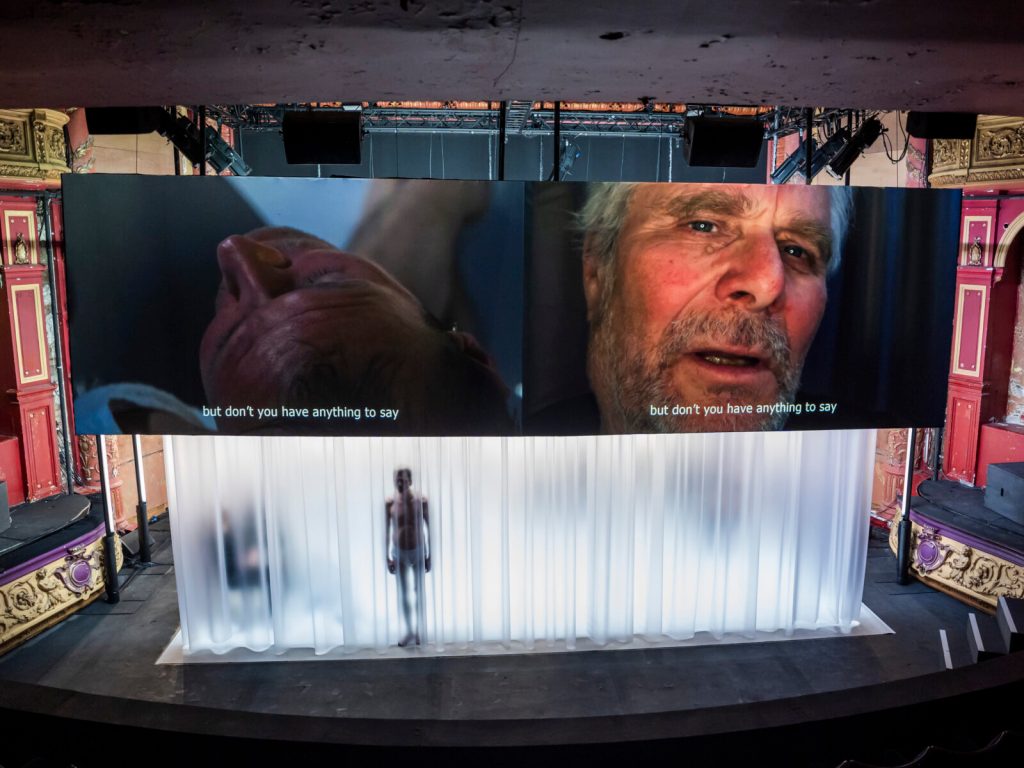

Photo by Johan Persson.

The Line of Beauty by Alan Hollinghurst adapted by Jack Holden – Almeida Theatre, London

Alan Hollinghurst’s much-loved novel, The Line of Beauty, won the Booker Prize in 2004. Looking back to the rise of Conservative politics in 1980s Britain, and the parallel AIDS crisis, it explored gay life and consciousness through the eyes of ingenue Nick Guest, who learns a lot in a short space of time. Now, adapted by Jack Holden and directed by Michael Grandage, it reappears two decades later on the Almeida stage.

Adapting novels as plays can be a thankless task, especially when they’re well known, but Holden does a good job in not allowing the book to kill the drama. Covering the period between the Conservative victories at the 1983 and 1987 elections, the play dramatises the collision of personal and political from the perspective of Nick, played engagingly by Jasper Talbot and his experiences in love, and while lodging with the family of a Conservative MP. Performances are universally strong, and Grandage’s production is very tightly delivered. Alistair Nwachukwu gives a standout performance as Nick’s first lover Leo, charming, clever and vulnerable. Arty Froushan, as cocaine-snorting playboy Wani, Charles Edwards as smooth, fatherly MP Gerald Fedden, Robert Portal’s menacing Badger, and Ellie Bamber as bipolar Cat Fedden are all excellent performances. Hannah Morrish channels the demeanour of Fergie in a way that is both hilarious and disturbing. Doreene Blackstock, as Leo’s mother, and Claudia Harrison as Gerald’s wife are also very strong, but their roles are rather limited – a problem with both book and play. The staging is sumptuous – sets and costumes by Christopher Oram – who has clearly delighted in recreating and subtley parodying the high society 1980s with its odd combination of frumpiness and glamour.

Some of the more literary aspects of the book get a bit lost in the dramatisation, such as the thematic significance of Henry James and of the ogee, a shape which swings both ways. What is more significant is how much of a period piece the play feels. Hollinghurst was writing about a period 20 years earlier, a time now approaching half a century from the present day. The key issues of the time – homophobia, social conservatism, privilege and the devastation wrought by AIDS should not be forgotten, but are not undiscussed. The play offers a highly professional and entirely entertaining evening, but it is unclear exactly why this novel needs to be staged at this particular moment.