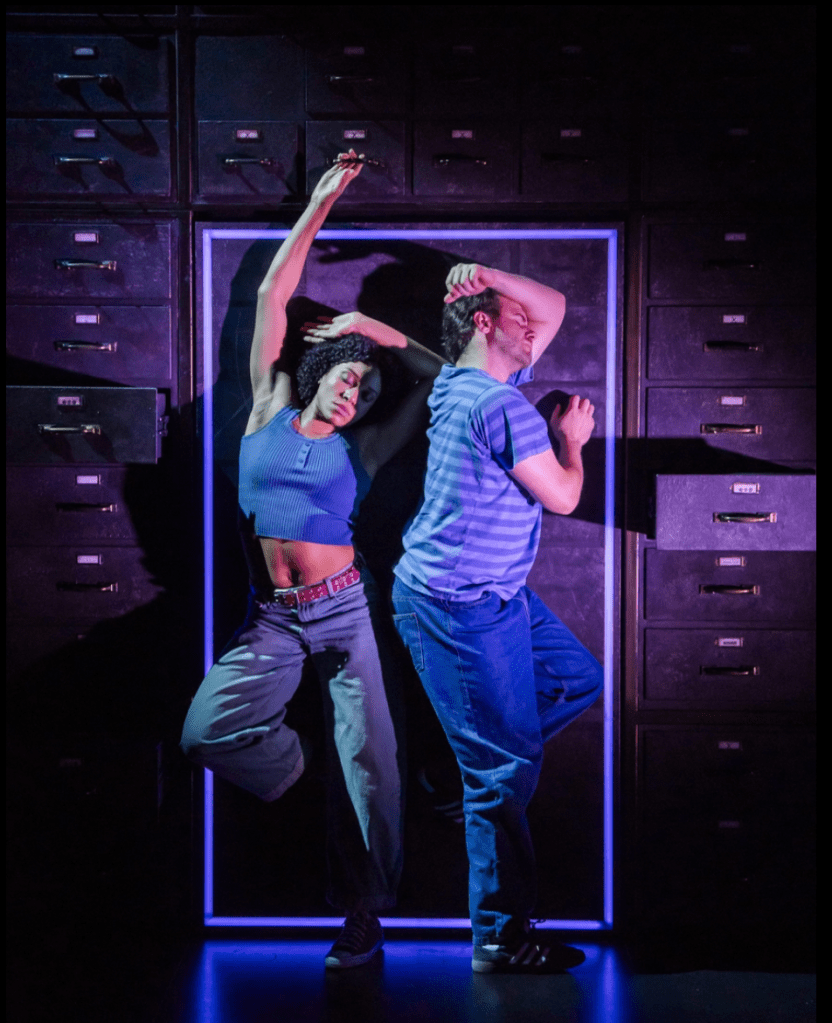

Jacoba Williams and Jonny Khan.

The Shitheads by Jack Nicholls – Royal Court Theatre, London

For starters, Jack Nicholls’ play The Shitheads is set in the Stone Age – specifically, the end of the Stone Age. I can only think of one other play with Stone Age scenes – Alistair McDowall’s The Glow, also staged at the Royal Court. It’s a bold and decisive approach from a writer who sent his work to the Royal Court on spec: they are staging submitted plays as part of their 70th anniversary season. Anna Reid has turned one end of the the Upstairs theatre into the interior of a cave with rock walls that are pretty convincing. It’s hard to make stage rocks that look real. But that’s only part of the setting. The play also uses puppets by Finn Caldwell, beginning with an elk hunting scene. The elk, real size, is operated War Horse style by two people, under puppetry captain Scarlet Wilderink. But this is definitely not War Horse. Nicholls creates a strange and thoroughly disturbing parable about inward-looking societies, fear of outsiders, resistance to change and violence which is entirely current.

The cast are all very watchable and convincing, at ease in their strange, compelling roles. The protagonist Clare is played by Jacoba Williams, a young woman venturing outside the cave where her father Adrian, played by Peter Clements, dictates the world view. Her sister Lisa, played by Annabel Smith, seems innocent but is capable of upending everything. Then a strange arrives – first a hunter, Greg (Jonny Khan), then his wife Danielle (Ami Tredera) who comes looking for him with their baby. The latter is the play’s other puppet, and possibly the most sinister thing in the whole evening. There’s competition for this: the cave is decorated with flesh and bones and the cave dwellers’ deceased mother is in a pit, along with discarded animal carcasses. Cannibalism features. Clare, asked why she lives in a cave, says “Because we’re very lucky” – but things are changing. The people they described as ‘Shitheads’ roam from place to place for better food and climate, and they’re leaving for good as the weather changes. The cave dwellers are doomed, but that may not convince them to change.

Directed by David Byrne, The Shitheads is a riot. The play, written in deliberately contemporary language, is very funny in a Martin MacDonagh, black comedy style. The idea of Stone Age characters called Adrian or Danielle is, in itself, very funny. The scenario also carries echoes of Enda Walsh – plays such as Walworth Road, where a closeted family group creates bizarre rituals to keep the outside world away. Nicholls is a clever and exciting writer, and this collaboration with a Royal Court on a high has all the excitement of the dramas that originally made the theatre’s name. It shows us ourselves in totally unexpected, entirely recognisabel ways, and providing gripping , unclassifiable entertainment while doing so.