A Knock on the Roof by Khawla Ibraheem – Royal Court Theatre, London

Published at Plays International

The significance of Khawla Ibraheem’s one-woman play about life in Gaza has only intensified since its runs at the 2024 Edinburgh Fringe and off-Broadway. A Knock on the Roof is one of the starkest, most politically urgent pieces the Royal Court has staged for some time. The war in Gaza has put UK theatre in the spotlight, and not to its advantage. The cancellation by the Royal Exchange in Manchester of Stef O’Driscoll’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream over what have been described as ‘pro-Palestinian’ messages revealed a cultural fault line. It has fed into disputes involving leading industry figures and the Culture Secretary about theatre’s freedom to make political statements, especially on the Israel-Hamas conflict. The brutal events in Gaza have been notable by their absence from our stages, even as they dominate political discourse. In the midst of this, Khawla Ibraheem delivers a masterclass in political theatre. She communicates, with honesty, commitment, humour and self-awareness, the truth of life under siege in a war zone, where politics is not a choice but an all-consuming, everyday reality.

A Knock on the Roof, is both written and performed by Ibraheem. It is named after the tactic, adopted by the Israeli Defense Forces, of dropping a ‘small’ bomb on residential buildings as a five-minute warning to residents that a rocket is coming. Ibraheem plays Maryam, who has a young son, Noor, an aging mother and a husband studying abroad. Her daily existence includes keeping Noor out of the polluted sea, dealing with her mother’s nagging, and negotiating with an absent partner. It also involves escape drills. Maryam becomes obsessed with how far she can run in five minutes, and who or what she can carry, if the knock comes. She practices in the middle of the night, carrying a weighted bag to represent her son, hoping to get fitter, trying to create a scenario in which her family survives.

The constant, never-ending fear that attends Gazan life is both mesmerising and terrible. The concept of being on the alert 24 hours a day for a signal that death is imminent is a deeply distressing scenario, and also farcical. What would you really bring if you had just one bag? Would you choose clothes, or things that really matter to you? How far do you imagine you can run in 5 minutes? Which way would you go? And what if you miss the ‘knock’? The combination of the ordinary and extraordinary is excruciating, but Ibraheem also makes it funny. Her performance, committed, nuanced and physical, is a real success. She appears relaxed, hugging friends before the play starts, engaging in audience interaction, but she is laser-focused. Her writing is multi-layered, acknowledging absurdity as well as terror. We are entirely convinced as she describes what on the surface seems unrelatable, describing an extreme situation entirely in terms of human experience.

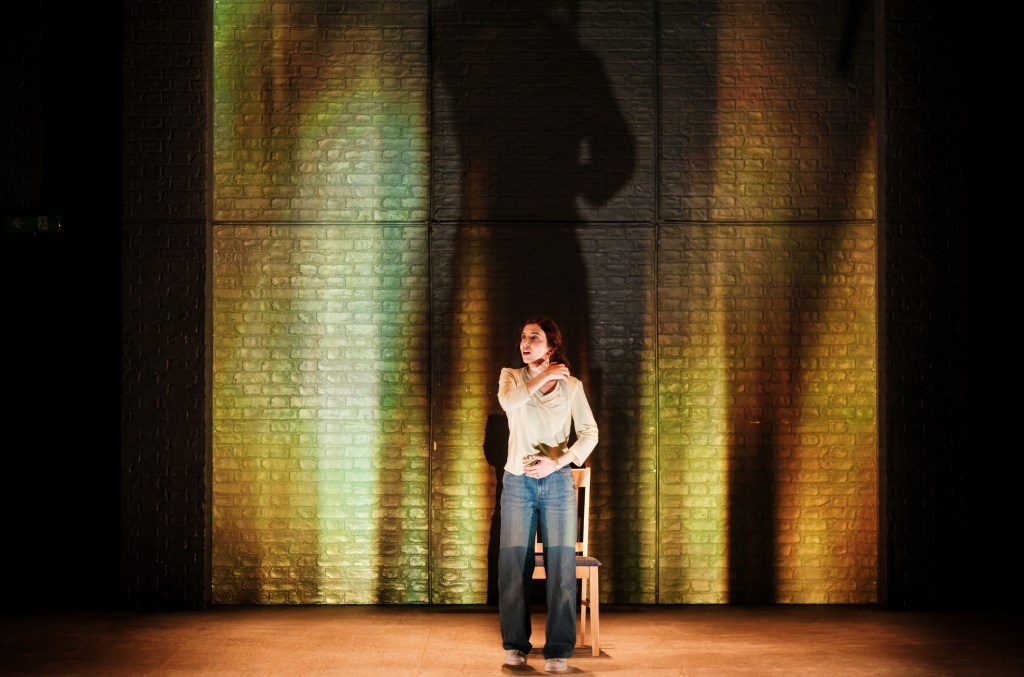

The play is also about more than the war, or the many previous wars – even Noor has already lived through two. Ibraheem writes about the frustration of being a woman in Gaza, with a child and husband neither of whom she really wanted, her studies and future curtailed. Her mother reinforces the social expectations that weigh her down, insisting she showers in a dress so she is not pulled naked from the rubble if the building is bombed. The focus is entirely on her performance. The stage is bare apart from a single chair, and settings are shown through light-touch back projections on the bare brick of the back wall – set designs by Frank J Oliva, and projection design by Hana S Kim. Director Oliver Butler developed the piece with Ibraheem, and together they conjure a place we find hard to comprehend from nothing with enormous skill. Ibraheem uses her body to communicate the sheer physical demands of survival in a war zone.

A Knock on the Roof is a significant show for a number of reasons. Staging such a stripped-back piece in the Royal Court’s main auditorium is a big and bold statement. Khawla Ibraheem is not only a significant talent, but a performer we need to hear from right now. And she blows away the fog of political argument and disinformation by showing what it is like to live in Gaza – something that, despite many months of press coverage, we still do not really know. The message she communicates is undeniable, that what happens to people is the only thing that matters. Away from slogans, this is surely the most meaningful lesson we can learn from disastrous conflict. If theatre cannot communicate this, it has no role; but by staging this show Artistic Director, David Byrne, makes it clear that he understands where the Royal Court’s power lies.