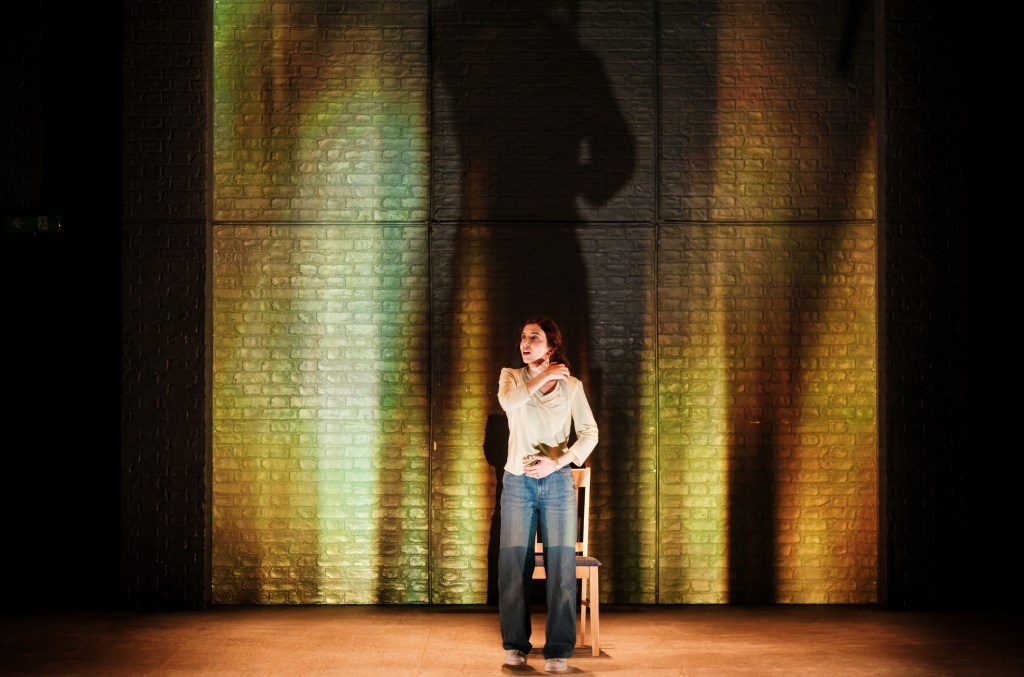

Cate Blanchett as Irina Arkadina (c) Marc Brenner

The Seagull by Anton Chekhov – Barbican Theatre, London

The quadbike which Simon Medvedenko (Zachary Hart) rides onto the stage at the start of Thomas Ostermeier’s production of The Seagull makes a statement straight away about the type of evening this will be. Ostermeier, true to form, strips away the play’s morose, stuffy pre-Revolutionary setting and makes it about the here and now. He has a point: this is something directors are reluctant to do with Chekhov, who still inspires the kind of reverence we long ago got past with Shakespeare. It makes for an entertaining but wildly inconsistent evening.

Hart, having got off his bike, pulls out an electric guitar and sings some Billy Bragg. The microphones that stay on stage throughout are used to address the audience directly, on the basis presumably that everyone is giving some kind of performance. Ostermeier’s approach is to underline everything, which is superficially entertaining. but has the tendency to pull the play to pieces. Central to this is Cate Blanchett, who delivers a fully committed performance as Irina Arkadina but gives the impression of being in a different play, encouraged by alienating devices such as the catwalk attached to the front of the stage on which she drapes herself dramatically, separating herself from the intense drama building behind her.

The rest of the cast ranges from brilliant to ineffectual. In the former category, Paul Bazeley’s Dorn is destroys people without meaning to, and Priyanga Burford brings his occasional lover Polina to intense life with limited stage time. Tanya Reynolds is excellent as a willowy, emo Masha, too wise for her years. And Tom Burke as Trigorin has an intensity of disappointment with life and himself that is truly scary. On the other hand, Kodi Smit-McPhee never fires or convinces as Konstantin, and the climactic scene with Emma Corrin’s Nina, a part to which she does not well-suited, does not deliver chemistry or intensity. On the night I attended, Jason Watkins was unfortunately indisposed and not playing Sorin.

The adaptation, by Duncan Macmillan, sets out to bring the play, leaping and shouting, into the 2020s, showing us it has as much to say now as it did in Chekhov’s era. However, this is never a subtle process, albeit full of energy, and when we hear actors raging about how little theatre doesn’t matter to ordinary people, it’s hard not hear a background hum of self-congratulation at just how self-ware everyone is. And Chekhov speaks to people on a human level, communicating political and existential issues in the frustrations we can all identify with. Macmillan and Ostermeier seem intent on making The Seagull something it isn’t.

There are powerful scenes including, surprisingly, the use of ‘Golden Brown’ by The Stranglers to punch home the sadness of a happiness that has entirely gone. Magda Willi’s clever set is simply a dense patch of maize stalks, from which characters emerge, sometimes addjusting their clothing, and into which they vanish again. But the show as a whole seems somewhat misguided, both in terms of concept and cast.