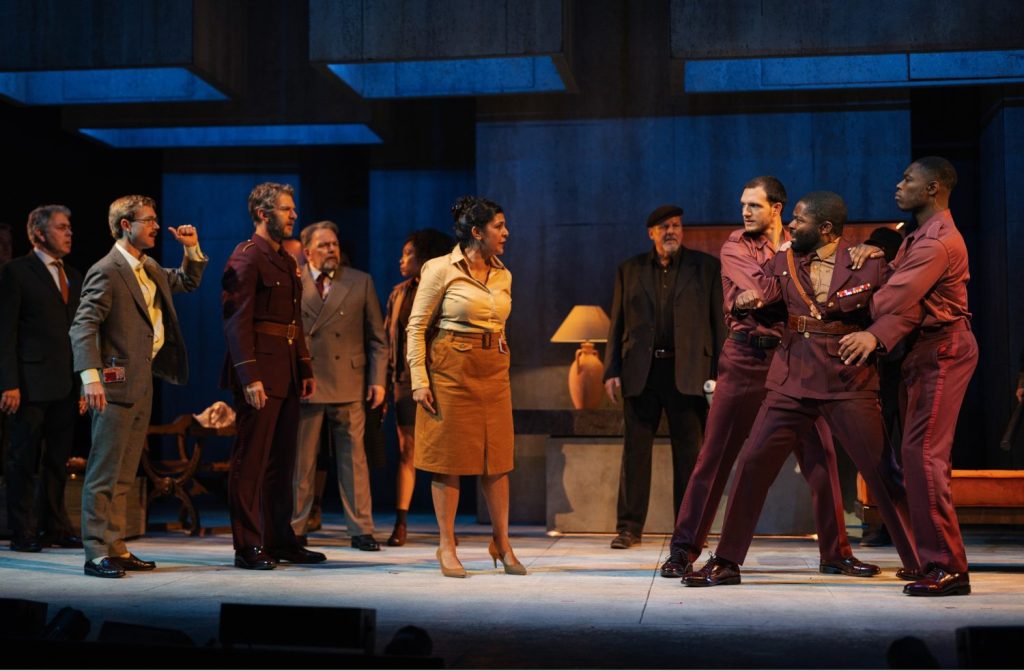

Sutara Gayle. Photo by Harry Elletson

The Legends of Them by Sutara Gayle AKA Lorna Gee – Royal Court Theatre, London

Published at Plays International

Sutara Gayle has had quite the life. Her one woman show expresses remarkable experiences through powerful, focused theatre. Gayle, born in Brixton, is a musician, singer, DJ and British reggae pioneer. She has lived in New York, opened for Shabba Ranks, spent time in Holloway Prison, and changed her name during a spiritual retreat in India. Her brother Mooji is a Hindu guru. Her sister Cherry’s shooting by police triggered the 1985 Brixton Riots. The Legends of Them combines music, film (projections by Tyler Forward and Daniel Batters) and a swirling array of characters, all played by Gayle, into a journey of awakening and discovery.

Gayle is also an actor, with a long career on stage and in film and television. This is the one aspect of her life she does not mention, and there is no need because it is obvious. Legends of Them is a performance tour de force. Gayle plays a long list of people she meets across eras and places – from Linton Kwesi Johnson to school friends, taxi drivers, dominoes players and policemen – who pass across the stage and through her life in sometimes dream-like fragments. She conveys each scene with minimum fuss and the maximum skill, using a vocal intonation, a tilt of the head, or a flick of the wrist. Gayle makes it look easy, but her performance is a masterclass in storytelling, from which other, far less subtle one-person shows could learn at lot.

The Legends of Them conjures up lost eras and events, knotting them loosely together as the bigger picture emerges, piece by piece. Although Gayle is the connecting presence, the show is explicitly about four legends in her life: her mother Euphemia, sister Cherry, brother Mooji, and the 17th century Jamaican freedom fighter, Nanny of the Maroons. Euphemia, who came to Brixton from Jamaica, brought up eight children, and pounded out living from her sewing machine. Cherry, who died in 2011, found herself thrust into the national news in disastrous circumstances, which she handled with great dignity. Her older brother Mooji is her guiding light, imparting Buddhist wisdom that helps Gayle see beyond tragedy and turmoil in her life. And Nanny is part of a suppressed history of resistance to empire, fighting the 17th century British occupation of Jamaica, and giving identity to those fighting the same battles today.

She threads together their stories expertly, never over-explaining but giving the audience enough to understand what is happening and why it matters. It is a high-wire act completed with supreme confidence, co-created with director Jo McInnes and dramaturg Nina Lyndon. Then there is the music. Gayle is a highly versatile writer and singer, and she sings at key moments. The set is dominated by a vast speaker stack covered in disco lights, which flash a backdrop to the action. Gayle strides on stage and immediately shows us what she’s capable of with her trademark reggae MC delivery, immediately raising excitement levels to eleven. Having established her formidable skills, she uses her full range, singing charming numbers influenced by pop and gospel, written with composer and musical director Christella Litras. She expresses herself directly and truthfully through music, which is clearly an essential part of her existence, and drives the show.

Gayle, with her collaborators, conjures an evening which is subtle, carefully woven, and at times exhilarating theatre, but it is more than that. The Legends of Them is a big success for the still-relatively-new Brixton House theatre, where it was first performed before moving the Royal Court – taking a show which is Brixton through and through into Belgravia. But it is more than a theatre production. Sutara Gayle’s life tracks the Black experience in Britain, through the terrible personal impact of racism and sexism, to personal fulfilment and self-knowledge. She is a local heroine, but her voice reaches far beyond SW9. She speaks from long, tough experience, and The Legends of Them sends a message which is proud, loud and clear.